17 foundational editing techniques for film and video editors

December 2024

11 mins

Want to tell compelling stories on screen? Experienced editors will tell you it starts with mastering the fundamentals.

Film and video editing techniques are a shared visual language that audiences instinctively understand. Each technique communicates a specific idea or evokes an emotional response.

As a film editor, the real skill is knowing how and when to wield them effectively.

Once you’ve mastered the rules, you can break them — bending editing techniques in film to surprise, captivate or challenge your audience. To keep them on the hook.

From continuity to jump cuts, understanding these foundational editing techniques will help you captivate any audience. Let’s dive in.

These 17 essential editing techniques are the building blocks of storytelling in film editing. Next time you notice an interesting edit, try to break down which techniques are being used and why.

1. Continuity editing: a foundational video editing technique

The most basic of all video editing techniques, continuity editing is used to match time, space and action across cuts to create a seamless flow.

For example, a person is sitting in a chair when they stand up and walk to the door. As the person stands up, we cut from a close-up to a wide shot, and the action flows smoothly across the cuts. They’re not suddenly at the door or halfway across the room. Everything is seamless.

The critique of continuity editing is that there can be “too much shoe leather” in a scene. We don’t necessarily need to see them do all that walking and door opening — we could just cut to them arriving at the place they intended to go to. As the audience, we do all the traveling in our heads.

In the bathroom fight scene from Mission: Impossible Fallout, there are lots of examples of matching action across cuts. It’s just more interesting than someone walking to a door!

2. J & L cuts: create smooth dialogue

J and L cuts are named after the shapes they create on the editor’s timeline.

For example, in a J cut the audio from the previous shot starts before the video cuts to the source of that audio. And vice versa for an L cut.

J and L cuts are most often used in dialogue scenes to create a rhythm between the two people talking and listening. If we just cut back and forth when each person talks it can feel like we’re ping-ponging back and forth relentlessly.

In this example from David Fincher’s The Social Network, there are lots of little J and L cuts as the dialogue shoots back and forth.

3. Cutaways: add depth and context to your film edits

Cutaways, sometimes called insert shots, are used to cut away from the main action and add depth or context to a scene.

For example:

In interviews, cutaways might show old photographs of a memory being described.

In scripted drama, a cutaway might reveal what a character sees when they open a drawer.

Cutaways can also add texture, such as showing what a character sees outside a car window while traveling.

Directors like David Fincher and Christopher Nolan insist on shooting their own cutaways as part of the ‘first unit’ (the main camera crew) rather than letting a second unit shoot it themselves later on.

The example above from Christopher Nolan’s Insomnia features a lot of small insert shots, showcasing how they can be used in storytelling.

4. Match cuts: key editing technique for seamless transitions

Match cuts are a video editing technique that match the framing of the central point of focus whilst jumping in location, time or both.

In this example, YouTuber Natalie Lynn describes how she created a series of match cuts of her climbing down from her van, across a series of different locations. This creates the sense of her traveling over time, even though it has the appearance of a static shot.

Filmmaker Edgar Wright famously uses match cuts in most of his films, including this one from Baby Driver.

5. Jump cuts: for fast-paced storytelling

In contrast to a match cut, the jump cut deliberately chops out parts of the action, or moves the character through time and space in a ‘jumpy’ way.

The impact depends on how the edits are joined.

Random or widely spaced jump cuts can evoke confusion or tension. In contrast, fixed-camera jump cuts — such as showing someone loading a gun or packing a bag — create energy and momentum, without the disorientation of changing the angle or location.

This sequence from Denis Villenueve’s Arrival features a series of cutaways to create the sense that the main character is thinking of her daughter and a jump cut at about the one-minute mark.

By trimming shots and juxtaposing fragments of scenes, editor Joe Walker injected urgency and resolved pacing challenges without losing key details. Read the full story behind the creation of the scene here.

6. Montage: an iconic video editing technique

Possibly the most iconic of all editing techniques, the montage is when a series of shots are cut into a unified sequence that elapses over time, very often set to a piece of music.

For example, a team getting ready for action, or training for a fight. A montage can often combine a series of match cuts, jump cuts and other editing techniques to create a sense of progression throughout the sequence.

Montages are often used to compress lengthy sequences down into a more engaging length. The best ones tell a story with every cut and every component.

7. Smash cut: attention grabbing video editing

A smash cut is an abrupt cut with a dynamic contrast on either side of the edit. This might mean cutting from a quiet scene to a suddenly very loud scene, or for a jump scare, like the Gandalf example above.

The change in volume and intensity takes us by surprise.

Smash cuts can also be used to surprise the audience by cutting abruptly from the end of one action that is anticipated — say a knife coming down in a murder — to a knife cutting vegetables.

The subversion of our expectations also takes us by surprise.

In this example, there is a smash cut from a mother screaming to Jeff Goldblum yawning as the screeching train brakes echo the sound mother’s scream across the edit.

The goal of a smash cut is to make the change as abrupt and surprising as possible. Sometimes, this is used for comedic effect, such as when a character says one thing, and we cut to them doing the exact opposite in the next shot.

8. Cross-cutting: build tension

Cross-cutting is a film editing technique where we switch back and forth between actions happening simultaneously — like a house on fire and the fire brigade rushing to save it — or between separate scenes.

Christopher Nolan’s films,The Dark Knight, Inception and Interstellar are masterclasses in cross-cutting. A breakdown by Lessons from the Screenplay, highlight’s how Nolan uses the power of cross-cutting — and shows what happens when it doesn’t quite land.

9. Parallel editing: compare stories and create contrast in film

While parallel editing and cross-cutting may seem similar at first, they actually serve different purposes. With cross-cutting, the goal is to build narrative momentum towards the climatic collisions of these two events.

Will the fire brigade arrive at the house in time to save the people trapped inside? Will Batman defeat the Joker in time to save Rachel? The audience is holding both threads together in their minds.

However with parallel editing, the goal is to create a comparison between the two narratives being shown. For example, we might see the rise of one character and the simultaneous fall of another. By cutting back and forth between their different lives, we understand the contrast.

The 1998 movie, Sliding Doors is essentially all about parallel editing.

10. Wipes: create seamless transitions in film and video editing

While Star Wars is famous for many things, one of the editing techniques it’s most famous for using are wipe transitions.

In the original Star Wars film, the wipes are mostly aligned to the same direction and movement as the action in the frame. For example, the image wipes from the bottom up as they lift C-3PO upwards, or a character crosses the screen from right to left, and the wipe follows behind them.

In some ways, wipes are a visual way of saying ‘meanwhile’ and serve as a slower transition than a direct cut, which can help the audience to move from one location, time and plot line to another.

Wipes like these were more commonly used in the kinds of Saturday morning adventure shows that Star Wars is famously inspired by.

11. Cross dissolves: a versatile editing technique

Similar to a wipe, a cross-dissolve is a common transition that film editors can use to artfully move from one shot to another. They can also be used more rudimentarily to mash together a cut that isn’t otherwise working.

As the old saying goes “If you can’t solve it, dissolve it.”

But longer slower dissolves like these in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining tend to work best.

12. Transitions: a complex technique

While wipes and cross dissolves are simple transitions to execute — sometimes planned with overlapping visuals that match across the two shots — transitions are much more complex and require pre-planning on set and in the edit.

The transitions in Scott Pilgrim Vs The World are all brilliant examples of what’s possible.

These video editing techniques involve creative uses of composition, compositing, visual effects and more.

The match cut video from Natalie Lynn also showcases some of her creative transitions which are well worth studying. The scene transitions in Michel Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind are also well worth a look.

13. Invisible and hidden cuts

Sometimes the best editing is the one you can’t see.

Hiding a cut in a whip-pan, or when a character fills the frame, are useful techniques for combining two different takes together as if they were one seamless shot.

1917 and Birdman are recent examples of ‘one shot’ films that aren’t actually filmed in one continuous take. Sometimes visual effects are used to stitch two different takes together in a composite on screen, while at other times cuts can be hidden in transitions through door ways or into darkness etc.

14. Split screens

The video editing technique of using a split screen to show two or more shots at the same time has been around for almost as long as cinema has existed.

The classic example is to use it to show both sides of a phone call, bringing the characters together on screen, heightening the intimacy of the moment, even if they’re miles apart.

Using a split screen this way works best when the original footage is shot with the technique in mind. For example, aligning eyelines so one character on the left looks right, and the other on the right looks left, creates a natural flow across the frame.

The TV series 24 made heavy use of split screens to remind the audience of the different simultaneous plot line and the current countdown.

Invisible split screens serve a different purpose. David Fincher is famous for using this kind of split screen to combine different takes from different portions of the screen to be able to craft the very best combined performances and timings.

At the end of this short breakdown by editor Kirk Baxtor you can see how he’s used a split screen to speed up one character’s listening shot, while also keeping the background action at normal speed.

15. Overdub: layer sound and visuals

This film editing technique uses what we’ll call an ‘overdub’ to show us one thing and let us hear another. Often this is used to hear the main character’s inner monologue during a scene, such as this profanity-laden example from Adaptation.

In the example above, from Annie Hall, a similar experience is created through the use of subtitles. They allow us to read the characters' real thoughts as they interact, leading to some comical juxtapositions.

16. Freeze frames: stop time in your edits

Film editing is all about manipulating time. And there’s no greater manipulation than to stop it all together. The freeze frame is in many ways an anathema to cinema which only works because 24 still frames zipping past our eyes every second creates the illusion of motion.

Freeze frames are most often used to give further time for narration to play out underneath the still image. Often this gives greater weight and impact to a moment of decision and what is about to happen next — either when the picture keeps moving out from the freeze frame, or when we cut to whatever comes next.

Typically, the still frame is paused on a dramatic action, such as the explosion in Goodfellas. But in the example from The Big Short (above) the seemingly randomly chosen frames add to the off-the-cuff texture of the film.

17. Not cutting: a powerful editing technique

Lastly, one of the most powerful editing techniques is simply not to cut at all.

By holding on shots while action occurs off-screen, or using long takes with a ‘moving master,’ the camera allows characters to move in and out of the frame, creating depth and a sense of immersion.

In this example from David Lynch’s The Straight Story, the film opens with an exceptionally long and slow shot, which tells the audience to re-calibrate their expectations for the speed of the story that’s about to unfold.

Another nice example of hidden cuts and extended takes is episode 7 of the hit TV series The Bear. The entire episode unravels in one long fluid take, adding to the ratcheting sense of chaos and conflict.

Behind the scenes, the editors of The Bear relied on LucidLink to seamlessly collaborate across locations. Get the lowdown on how the editors worked together from numerous locations here.

How to edit from anywhere

Modern editing workflows need tools that can keep up. Especially when teams working across locations face numerous remote video editing headaches.

But traditional collaboration methods like shipping hard drives or downloading files through sync-and-share tools can cause major disruptions:

Download delays: editors lose valuable time waiting for large video files to transfer.

Version control headaches: conflicting edits and duplicated files can derail progress.

Storage bottlenecks: legacy systems often can't scale to handle massive 4K or 8K files.

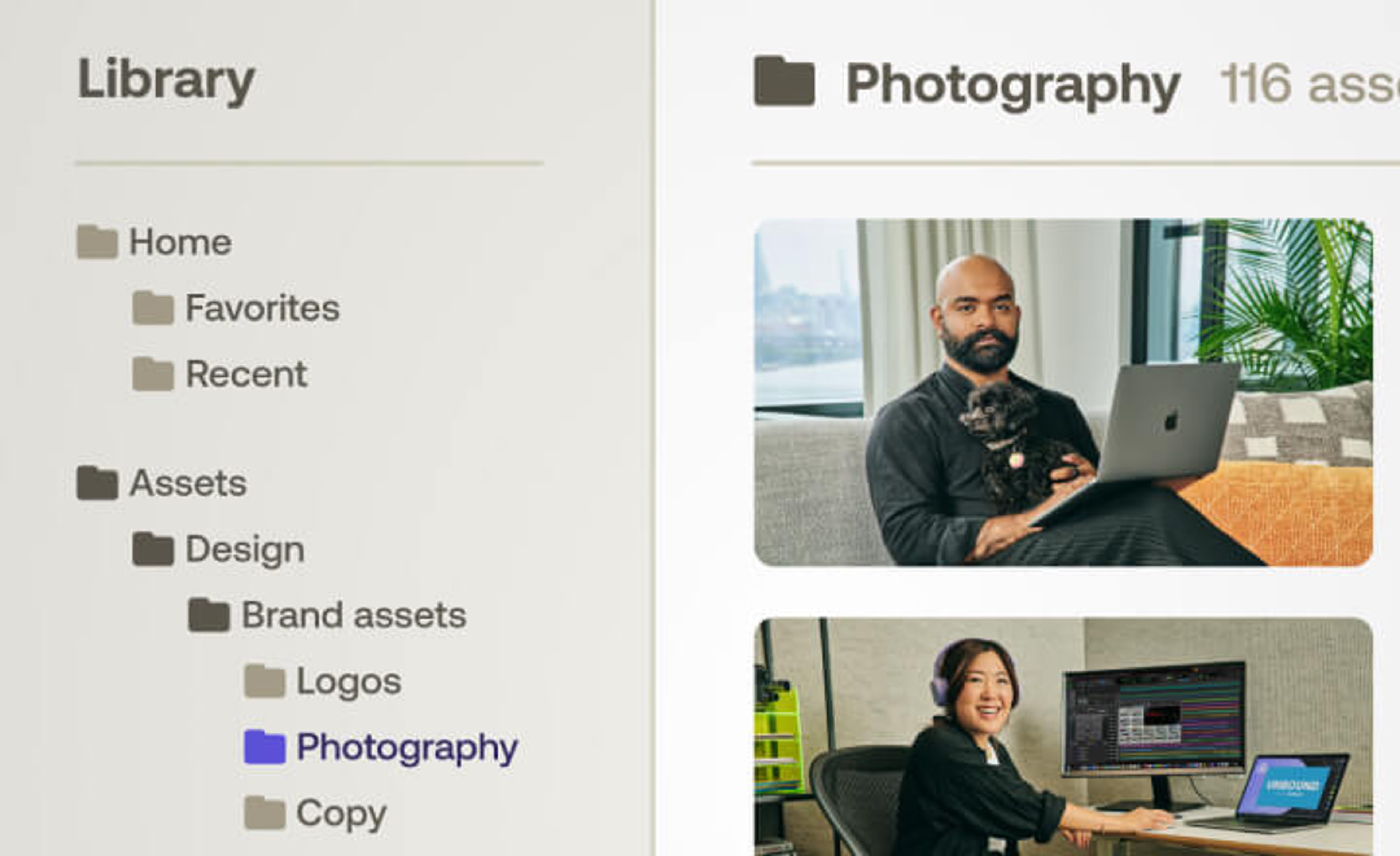

That’s where cloud solutions like LucidLink help. By streaming files directly from the cloud, LucidLink frees editors to:

Collaborate in real time: teams can access the same media instantly, without lengthy downloads or transfers.

Maintain version control: everyone works on the latest files, avoiding version conflicts.

Edit from anywhere: whether you’re in LA or London, it feels like you’re working from the same local drive.

That’s why editors on shows like The Bear and Atlanta rely on LucidLink to collaborate with their team in real-time, wherever they’re working.

Want to see how LucidLink can transform your editing workflow? Start your free trial today.

Keep reading

Marketing video production guide: how to stand out & get results in 2025

Discover expert strategies for marketing video production. Learn how to create standout videos that engage your audience and drive real ROI.

28 February 2025, 8 mins read

Remote video production: a step-by-step guide

Discover the challenges, steps and tools needed for remote video production. Get advice to create remarkable remote productions in our comprehensive guide.

14 February 2025, 10 mins read

Creative asset management: top tools and best practices

Explore creative asset management best practices and discover the best tools to streamline your creative workflows.

07 February 2025, 11 mins read

Join our newsletter

Get all our latest news and creative tips

Want the details? Read our Privacy Policy. Not loving our emails?

Unsubscribe anytime or drop us a note at support@lucidlink.com.